The world is now more than a year into the second global crisis of the century. Both the current pandemic and the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) more than 10 years ago tested the capacity of international financial institutions to respond with speed and scale. This time, the IMF has stepped up, first with emergency finance facilities, and later this year with a massive injection of global liquidity through a Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation of $650 billion.

But what about the multilateral development banks (MDBs)? One of their central roles is to expand the fiscal space of middle- and low-income countries (MICs and LICs) for development spending, exactly what is needed now, and to catalyze finance from the private sector, especially when private finance pulls back. Have they done so? As the 2020 data on MDB finance become available, what can we conclude about how MDBs are performing when the developing world needs them most?

While high-income countries spent on average 24 percent of GDP in 2020 to combat the crisis and its effects, MICs managed only 6 percent, and LICs just 2 percent. Yet the evidence is mounting that poor countries and the poor generally are much harder hit by the pandemic than they were by the GFC, with up to 150 million people projected to be pushed into extreme poverty by the end of this year. Moreover, as vaccines usher in a return to normalcy in the rich world, the slow pace of vaccine rollouts elsewhere means that in much of the developing world, the pandemic could get worse before it gets better.

Further, we know that even before COVID-19, poor countries were confronted by much greater spending needs to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) than their higher-income counterparts. According to the IMF, on average, LICs must spend an additional15 percent of GDP on health, education, and infrastructure needs related to the SDGs, compared to 5 percent of GDP in emerging market economies. COVID-19 has widened this gap even further. And we know that over half of poor countries are now in, or at serious risk of, debt distress, limiting their ability to borrow from non-concessional lenders in China or in the private sector.

So this is the right time to look at how the MDBs have performed so far during the pandemic (adding to the work of CGD colleagues) and to draw implications for their future roles in crisis response and in expanding finance available for critical long-term public spending.

This crisis versus the last one

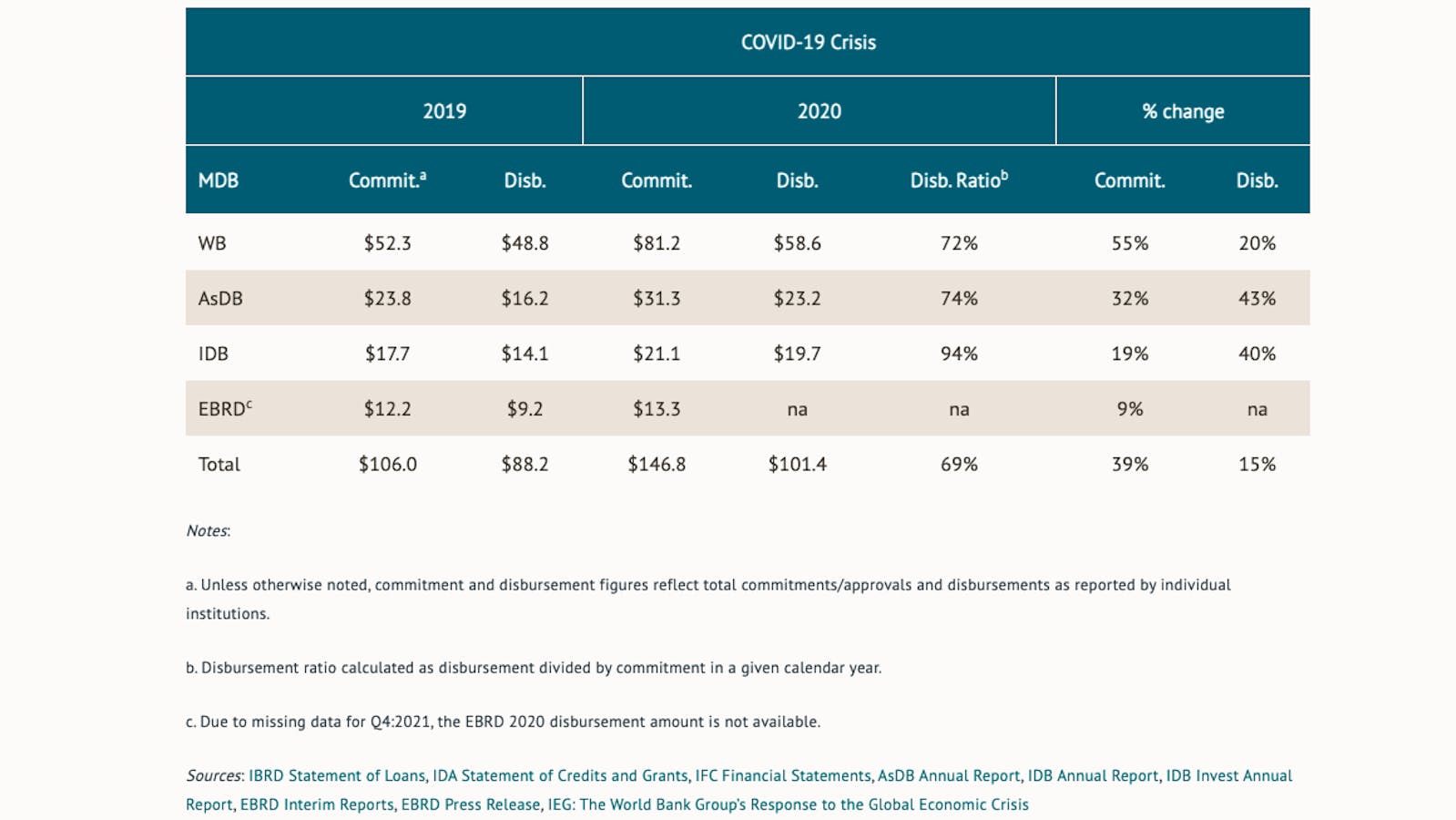

As shown in Table 1, MDB lending to governments did indeed increase significantly in 2020. Commitments by the World Bank and the major regional development banks rose collectively by 39 percent to about $145 billion (excluding the African Development Bank, AfDB, for which 2020 data are not available). Disbursements (funding actually received during 2020 by recipient governments) increased by a smaller 15 percent (excluding the European Bank for Recovery and Development). The top performers with respect to commitment growth were the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (AsDB), with increases of 55 and 32 percent respectively. The AsDB and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) managed to increase disbursements even faster than commitments, by 43 and 40 percent respectively. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has lagged, with commitments up only 9 percent.

Table 1. MDB commitments and disbursements (USD billions)

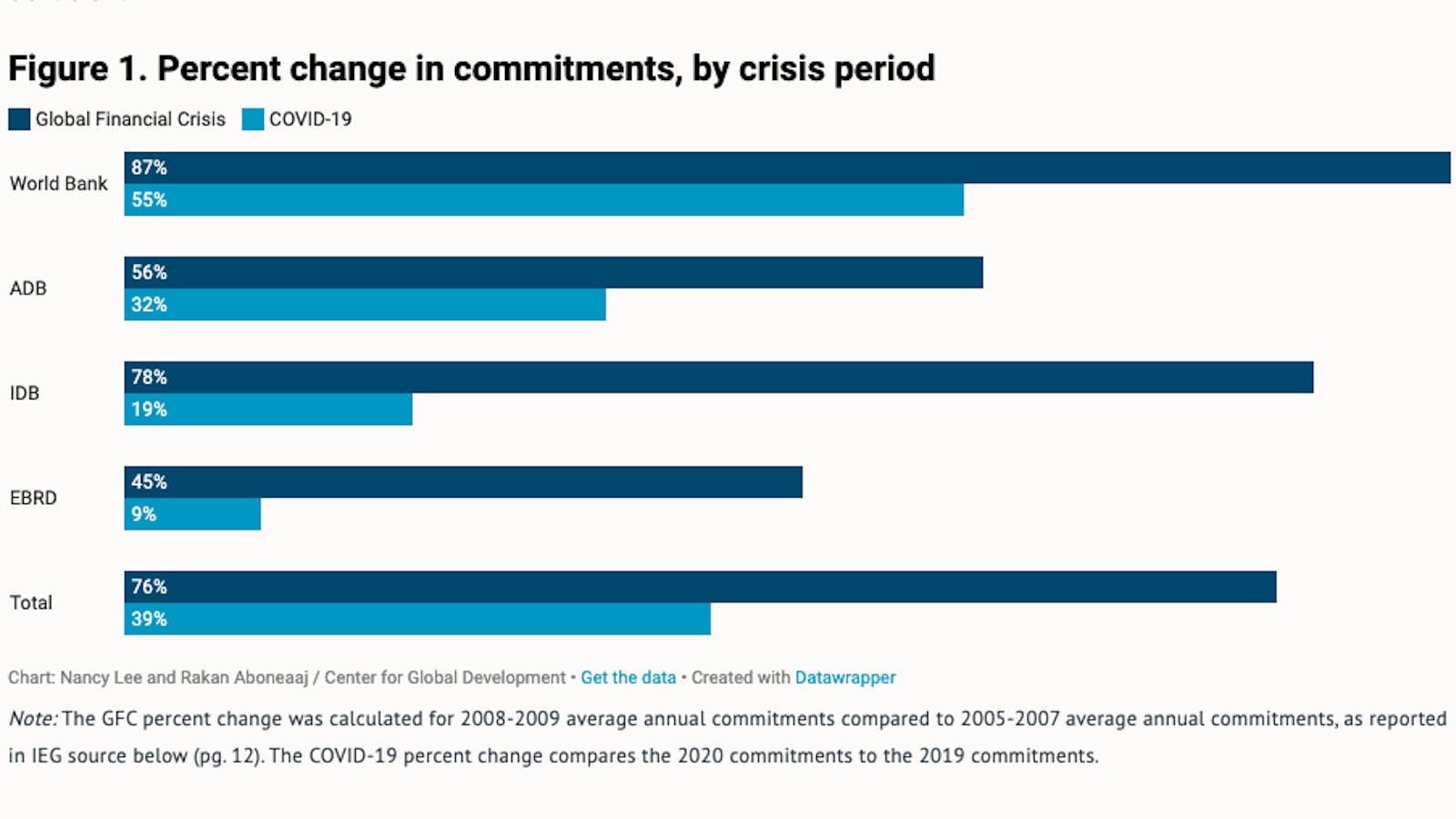

Yet that growth seems less impressive when compared to the GFC record. In that crisis, commitments by these institutions jumped 76 percent, with particularly strong performance by the World Bank, the AsDB, and the IDB (figure 1). The faster commitment growth in the GFC is not easy to explain given that developing countries, with the exception of emerging and developing Europe, have certainly been harder hit during the pandemic. In 2009, LICs’ and MICs’ per capita GDP growth slowed to1 percent year-on-year. But, in 2020, LICs and MICs experienced a3.5 percent contraction of per capita GDP, not just a slowdown. All of the MDBs analyzed here have received capital increases since the GFC, and there is a strong case for using the headroom they have on their balance sheets for a surge in lending during a crisis of this magnitude and duration.

A surge for governments but not for the private sector

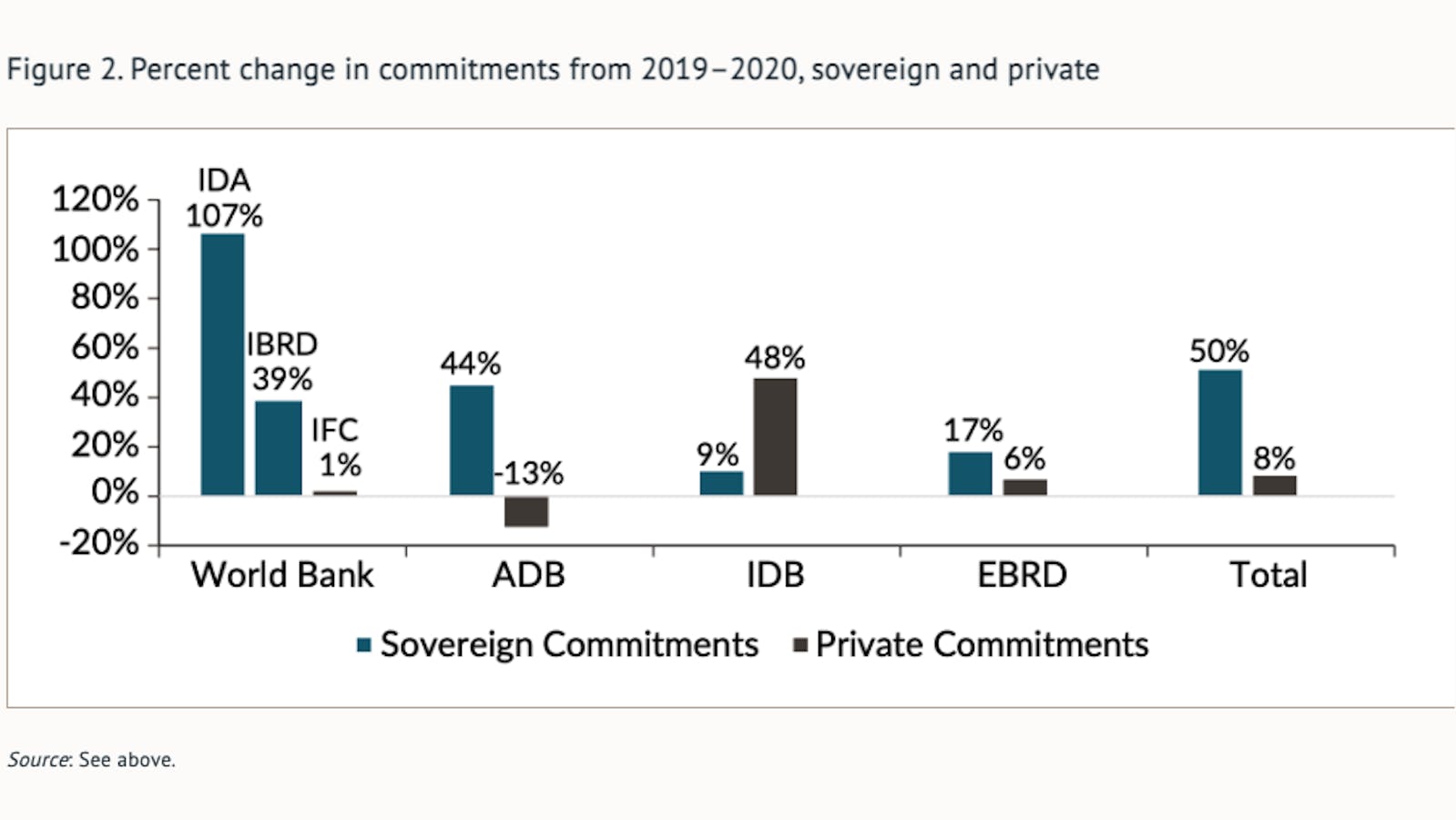

Figure 2 shows 2019 and 2020 MDB finance to the public sector versus the private sector. The differences are striking. Total MDB finance to governments rose by 50 percent. World Bank IDA commitments (concessional finance to poor countries) in particular grew by a whopping 107 percent, an encouragingly proactive response to pressing needs in poor countries. It is puzzling that IDB lending to governments in Latin America, the developing region hardest hit by COVID-19, rose by only 9 percent.

And the MDBs clearly struggled with their countercyclical role in private finance. Total finance to the private sector rose by only 8 percent. Surprisingly, IFC (the World Bank Group’s private finance arm) commitments were essentially flat, and AsDB commitments to the private sector fell (perhaps to make room for more sovereign lending since both public and private lending are on the same balance sheet for the AsDB). Only IDB Invest, the private finance arm of the IDB Group, excelled with 48 percent growth in commitments.

What does this evidence mean going forward?

The data suggest a smaller overall response to the COVID-19 crisis than the GFC despite the larger economic toll taken by the pandemic in most developing regions, uneven performance across institutions, and a weak outcome for private sector finance.

More analysis is needed as additional data emerge about performance by sector, country income groups, finance instruments, and regions. Making such comparisons across institutions unfortunately is now unnecessarily difficult and time-consuming given large differences in MDB reporting periods, frequency, and data definitions. For effective oversight, transparency, and accountability, shareholders can and should call for joint, timely MDB reporting.

But we can begin to draw some lessons for the future based on this evidence. Pending more analysis, here are three early observations.

1. The MDB system is not big enough to make a meaningful contribution to either crisis response or SDG finance, especially in poor countries.

Despite the 2020 increases, MDB lending in 2020 still totaled only 0.5 percent of the combined GDP of MICs and LICs, a drop in the bucket of their collective fiscal response and SDG finance needs.

Shareholders lack a credible, consistent methodology for determining the right size for individual or collective MDB capital or lending capacity. But a back-of-the envelope calculation illustrates one way to think about how much is enough lending capacity.

Recall that SDG finance gaps average 15 percentage points of GDP for poor countries, and LICs managed only 2 percent of GDP in fiscal response to the pandemic (compared to 6 percent of GDP for higher-income developing countries). So we could notionally set a goal for MDBs to collectively contribute 3 percent of GDP annually to the fiscal capacity of low-income (IDA-eligible) countries. That would amount to approximately $70 billion per year. For higher-income developing economies with more fiscal capacity and better access to private capital markets, we could target a much smaller 0.5 percent of these countries’ GDPs for the MDB contribution to crisis response and SDG finance, including climate finance. That would come to $160 billion per year. Together these two figures amount to collective MDB finance of approximately $230 billion per year—nearly 60 percent more than what MDBs (excluding the AfDB) actually committed in 2020.

2. MDB collective surge performance does not appear to be calibrated to the severity of the crisis.

In 2009, the GDP of developing and emerging economies grew 2.5 percent. In 2020, it shrank by 2.2 percent. Yet the size of the increase in collective MDB finance in 2009 was twice that in 2020. The reasons are unclear. Perhaps more united G20 shareholders in 2008-09 played a role in coalescing behind a more proactive response. Shareholders did step up to backstop MDB lending with capital increases across the institutions. Or the problem could be the administrative difficulty of quickly and significantly boosting finance to the large number of poorer countries affected by the pandemic, although IDA has apparently managed this challenge well. There might also be a problem on the demand side as those developing countries that can are choosing to go to private capital markets rather than the MDBs. Whatever the reason, it is clearly important for the future to examine how better to match MDB finance with finance needs.

A critical aspect of this examination has to be the division of labor between the IMF and the MDBs. The IMF can react with speed and scale and has rightly done so using its emergency finance tools. But its focus in crises is supposed to be primarily on external imbalances and financial stabilization, not budget support, climate finance, and vaccination funding. The fact that some are looking at the SDR allocation and the IMF as a source of funding for these things should be seen as a clear indication that, for whatever reason, the MDBs are either not able or not willing to meet challenges in these areas. At this moment and going forward, shareholders and vulnerable populations can ill afford a multilateral system that is not firing on all cylinders.

3. MDB private finance arms do not play a significant countercyclical role in crises.

It will be argued that private finance arms are better suited to the recovery phase, although it is too early to tell in this crisis whether they will step up as recovery takes hold. The counterargument is that the additionality and catalytic power of MDB private finance is at no time more obvious than in a crisis when risks exceed the tolerance of the private finance sector. Existing MDB private clients need more support to keep them afloat during sharp drops in demand and supply chain disruptions, and new clients need access to MDB finance as their usual sources dry up. Of course, in these circumstances MDBs would need to take on a lot more risk and face some damage to their balance sheets. It is not clear, certainly based on the data so far, that they or their shareholders are willing to do so. But if not, their business model is not that different from commercial banks, which raises questions about their added value as recipients of public capital.

It remains to be seen whether their financial instruments—especially their heavy reliance on senior lending—are not well suited to crises, or whether they need some off-balance-sheet structures that help them manage increased risk, or whether they can quickly ramp up transactions when their investment officers can resume travel. What is clear is that shareholders will be carefully considering where to put more public resources in the wake of the deep and lasting damage wreaked by the pandemic. It is hard to make the case for more capital to expand MDB private finance if it is only procyclical.

Time for a rethink

MDBs are an excellent deal for their shareholders—the capital contributions governments make are multiplied many times over in MDB lending capacity. But the evidence from the first two global crises of this century, as well as from worsening SDG finance gaps, only highlights the still-marginal role of the MDBs. This is the time for shareholders to think about rightsizing the MDB system and extracting greater returns from MDB assets, collectively and individually.