The impact of IMF adjustment programs on spending for education and health has been widely debated. Some have argued that austerity measures in the IMF programs have lowered such spending during programs. Others have shown that spending on education and health increased at a faster pace in countries with IMF programs than those without. These authors have argued that higher economic growth during the program period raises domestic revenues, thereby creating budget space for greater spending on social sectors. Furthermore, they contend that most programs in developing countries have IMF conditionality to shield education and health spending from austerity cuts.

In this blog post, I draw on a study that I recently completed for the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office. The study’s focus is on the broader issue of growth implications of fiscal adjustment undertaken in 131 IMF programs implemented during September 2008 and March 2020, covering low-income, emerging, and advanced economies. I also examined the state of education and health spending three years before, during, and three years after the programs had elapsed. I found that IMF conditionality in general helped to shield education and health spending from budget cuts in the short term, particularly during budget negotiations, but it did not succeed in significantly raising spending in relation to GDP over time. In this light, I argue that the focus of IMF conditionality needs to change to also achieve long-term increases in education and health spending.

Trends in education and health spending before, during, and after IMF programs

The 131 IMF programs I examined were supported by two types of arrangements: GRA (General Resources Account) and PRGT (Poverty Reduction Growth Trust). All IMF member countries have access to GRA on non-concessional terms, but only low-income countries can access concessional financial support through the PRGT. Currently, support through PRGT is interest-free.

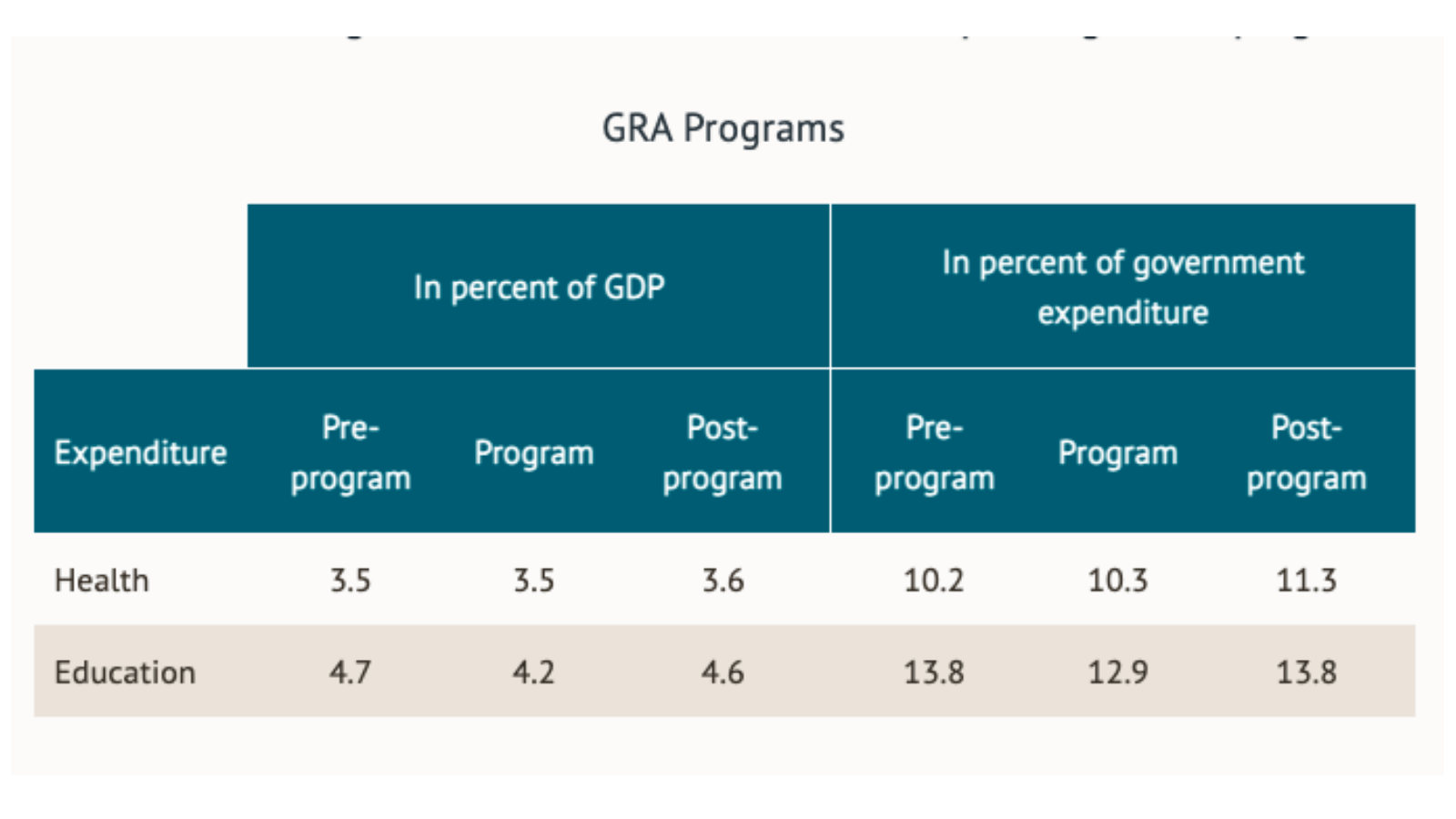

What I found is that trends in education and health spending before, during, and after programs differed between GRA and PRGT programs. On average, in GRA programs, the share of health spending increased somewhat in the post-program period (that is, three years after the program), both as a proportion of GDP and in the total budget, suggesting increased prioritization of the health sector in government budgets (Table 1). Further, health spending in GRA programs was protected during the period of the program. By contrast, the share of education in budget allocations remained unchanged in GRA programs in the post-program period but fell during the program period.

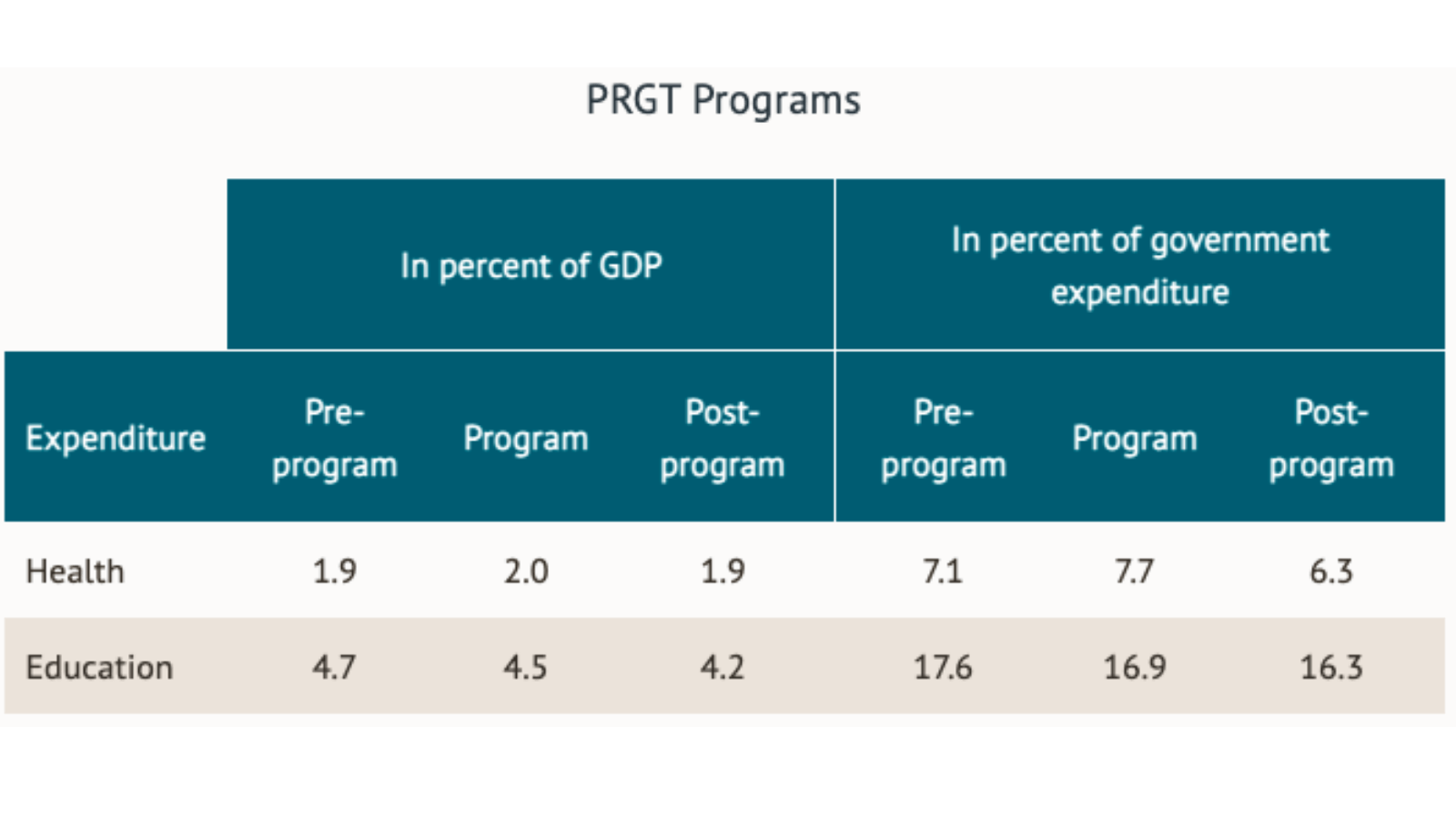

In the low-income countries that accessed PRGT programs, where social spending is relatively low, health spending remained unchanged as a share of GDP while spending on education declined somewhat after the program ended. The share of both sectors in budget allocations lessened. During the course of the programs, spending on health increased while that on education declined.

Table 1. Trends in government education and health spending in IMF programs. Sources: World Development Indicators; author’s calculations. Note: All figures are period average. "Pre-program" captures the three years prior to a program's starting year; "Program" captures program years; "post-program" captures the three years following a program's ending year.

Many programs are not completed in the stipulated period, often because targets are not fully met by countries. These programs showed particularly disappointing outcomes for health and education spending. This was particularly the case for PRGT programs where both spending categories fell in the post-program period vis-à-vis before the program.

What tentative conclusions can we draw from these results?

It seems that program conditionality targeted at protecting social spending from budget cuts in IMF programs has not contributed to raising spending on education and health in relation to GDP over time in both GRA and PRGT countries. Such conditionality, however, may have helped in shielding education and health spending from budget cuts in the short term. Since the ultimate goal is to raise social spending in low-income and many emerging market economies to help attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, it would seem that IMF conditionality should also place emphasis on policies that raise education and health spending over a longer time period.

Another recent study finds that conditionality included in programs to strengthen public financial management institutions has more substantive impact on raising social spending in the long term as compared to the short-term focus of conditionality that currently is put in place. Conditions on the accumulation of arrears and control over extrabudgetary spending, budget execution, and accounting and financial reporting are associated with higher health and education spending in IMF-supported programs. For example, a reduction in arrears and control over extrabudgetary spending leads to increased availability of resources for productive spending including spending on education and health. Thus, conditionality to strengthen public financial management practices and protect social spending in the short term could complement each other in securing a durable increase in social spending over time.

The bottom-line is that the short-term focus of current IMF conditionality to raise and protect education and health spending in IMF programs should be complemented with the implementation of policies that raise education and health spending over time. Without recognition of this complementarity, it will be difficult to witness sustained increases in social spending essential for meeting the SDGs by 2030.