The How, Who, and Why of Partnerships for Poverty Reduction: A Conversation with Karin Schelzig (ADB)

Published: February 24, 2022

Stakeholder collaboration and working together are crucial when it comes to adapting and implementing new approaches to poverty reduction. BRAC Ultra-Poor Graduation Initiative and its partners around the world bridge cultures, languages, ways of working, and even oceans in order to reach our collective goals to empower people living in poverty and facilitate their upward trajectory towards successful and sustainable livelihoods.

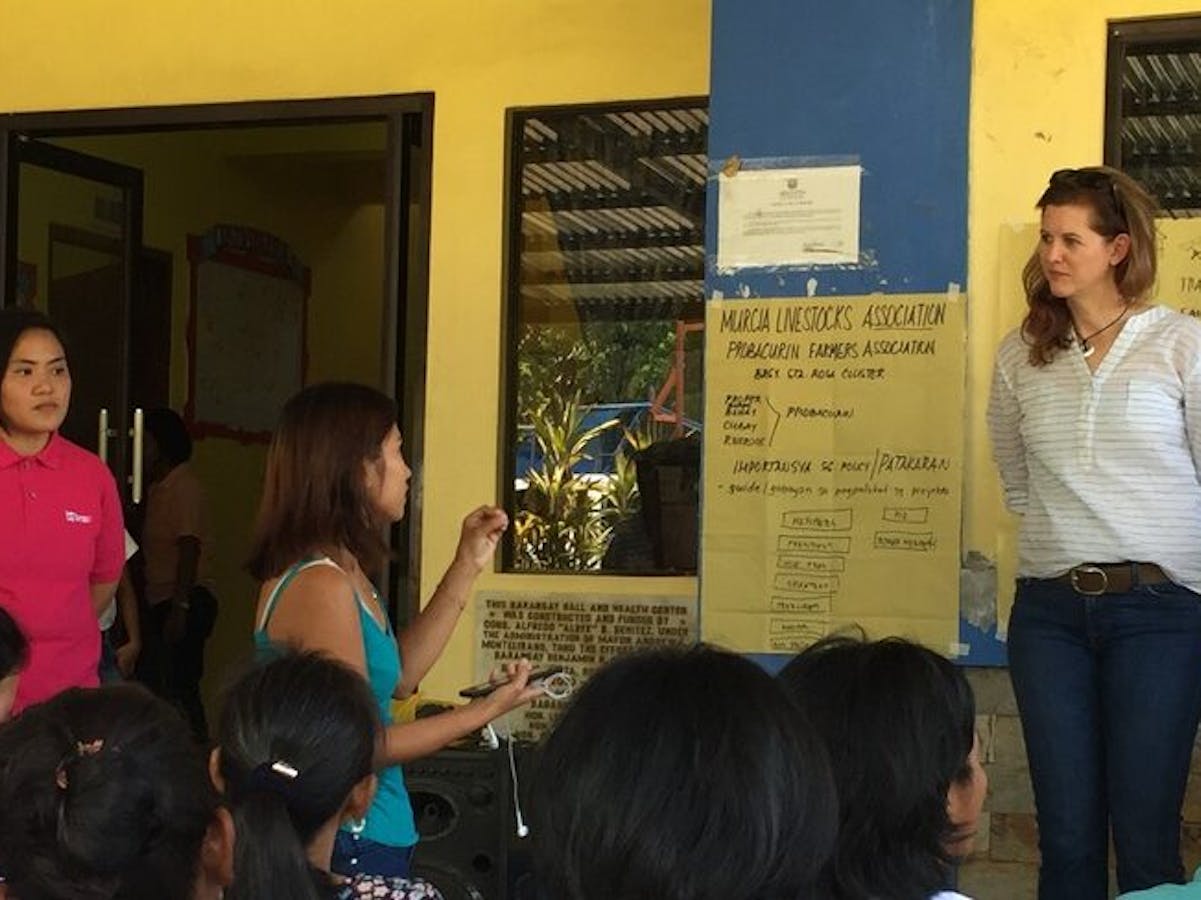

After our successful Regional Dialogues focused on Africa and Asia, “Applying Evidence to Achieve Long-Term Development, Poverty Eradication, and Inclusive Growth“, I had the opportunity to further dive into this topic and frame a more nuanced story of long-term partnership with Karin Schelzig, Principal Social Sector Specialist, East Asia Department at the Asian Development Bank (ADB). During this interview, Karin used the ADB’s recent experience introducing the Graduation approach in the Philippines which has been an incredibly collaborative project involving two government ministries, five local governments, four departments of ADB, and two NGOs.

Bobby Irven (B): Karin, before we dive into the how, who, and why of this project, as someone who has more than two decades of experience working in the social protection sector, what is one of the most surprising/significant changes you have seen as of late?

Karin Schelzig (K): It’s great to see how social protection has become much more of a development priority over the years, especially in the Asia Pacific region. In the early days there seemed to be a lot of reluctance, or skepticism, when it came to investing in social assistance, and especially in cash transfers. We’ve come a long way since then, thanks to all the empirical evidence that shows cash transfers work! We know that poor people spend the money wisely, that they invest in human capital, and that cash transfers don’t actually make people lazy. It was heartening to see that in the global response to COVID-19, almost every country very quickly introduced social protection measures, and the majority of those measures involved cash transfers.

B: Can you start off by telling us a little bit about how the Graduation pilot in the Philippines came about?

K: ADB’s partnership and policy dialogue with the Philippines in developing targeted poverty reduction and social protection solutions is decades-old, and ADB has become a long-standing and trusted partner. Over the last dozen or so years, we’ve provided several rounds of strategic financing and technical assistance for the country’s national conditional cash transfer program that aims to keep poor kids healthy and in school. By the middle of the last decade the cash transfer program had grown to reach about 4.5 million families, and it had been highly effective, but poverty rates in the country stayed stubbornly high and remained a major challenge.

Against this backdrop, in 2015, we introduced the idea of testing the Graduation approach by building on the cash transfer program to address multidimensional poverty, diversify household income sources, and build resilience to shocks. We wanted to add a rigorous research element to try to unravel whether group-based coaching and assets could bring program costs down without reducing the impact, as compared to individual coaching and assets. The policy dialogue and consensus building around the pilot and the impact evaluation continued through 2016 and 2017, and the pilot was eventually implemented from June 2018 to September 2020.

B: The Graduation pilot was, even by industry standards, a highly collaborative effort. Who were the different partners, and how did you all work together to make it such a success?

K: Broadly speaking there were six partners:

Implementation was led through the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) and the administrative systems established for their Kabuhayan (livelihood) program, which provides households with productive assets and technical training.

Second, since the pilot worked with 2,400 poor beneficiaries of the cash transfer program – managed by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), they were also a key partner and early on expressed interest in scaling up Graduation through their own sustainable livelihood program.

The third group of stakeholders were local government officials. The pilot participants were in 5 municipalities and 29 villages (or barangays), and close collaboration with local officials was of course essential to get anything done, and to sustaining the results.

The fourth partner was ADB, but behind the scenes, internally, there were actually several different groups involved. Our team mobilized bits and pieces of grant funding from wherever we could find it, from different divisions working on innovation, civil society participation, social protection, and economic research and impact evaluation. This required internal coordination with – and reporting to – several different departments.

Fifth was the BRAC Ultra-Poor Graduation Initiative, engaged by ADB to provide technical assistance, refine the pilot design, and run the day-to-day field implementation, including training and managing the program coaches

And finally, to underpin the pilot with a rigorous research agenda, we engaged Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) to design and carry out a randomized control trial impact evaluation so we would have solid evidence to share.

B: Lastly, while it may seem obvious to us, why, in your experience, are partnerships so important for this type of work, especially during times of upheaval like we’ve experienced during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis?

K: Simply put, different partners bring unique strengths to the table. In this case, each partner supported the pilot in different ways, from developing the approach and building consensus, to keeping it all going when things got a little rocky during implementation.

For example, when things stalled a bit after a change in leadership and changing priorities in our original implementing agency, IPA drew on their local relationships to help us anchor the pilot in the DOLE Institute for Labor Studies. This would never have happened without them.

Then, midway through the pilot, COVID hit. Just like almost everywhere, the impact in the Philippines was severe, with a loss of jobs and income and a rise in risky coping behaviors. Local lockdowns required quick thinking on how to adapt, and BRAC was able to respond by bringing extensive field experience and innovative approaches to bear – for example using the digital monitoring they introduced before the pandemic for quick data review to identify the households who were most vulnerable, helping them access extra support from our local government partners. BRAC was also quick to transition to a no-contact yet high-interaction digital outreach format since families were already used to frequent contact with their coaches.

When the pilot ended in September 2020, IPA adapted the research plan to do a rapid phone survey. The survey confirmed that households had of course suffered setbacks, but it turned out that the households in the graduation pilot, no matter which treatment arm they were in, fared significantly better than those in the control group, and across a range of dimensions – including financial security, food security, and mental health. These results are super promising, and no doubt a result of the strong partnerships that underpinned the work all along the way.

My colleague Amir Jilani and I wrote up the findings and evidence in a policy brief that is available online. The full-scale impact evaluation report will be available soon, looking at what happened two years after the interventions.

In exciting news, the Graduation approach is now being scaled up both at ADB, with a growing community of practice and new initiatives in several countries, and in the Philippines, where it is well on its way to becoming an integral part of the DSWD Sustainable Livelihoods Program. And a new partnership with the Australian Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade has brought both grant financing and vast technical experience in productive inclusion efforts. We’re looking forward to being able to report more positive results!

Read more expert insights: Responding to New Threats to Poverty Eradication in Asia