The three changes we need to improve understanding of private capital mobilisation

Published: November 08, 2023

BYPAUL JAMES|NOV 8, 2023|BLOG

This year’s World Bank Annual Meetings in Marrakech largely focused on how the Bank could be bigger, better, and faster in the face of the polycrisis and global challenges that we face.

One important development during the event was the publication of the second volume of the G20 Independent Expert Group (IEG) report “The Triple Agenda”. Taken together with the first volume, the report offers a blueprint for how multilateral development banks (MDBs) can be scaled effectively to increase lending to emerging and developing economies (EMDEs). Central to the reports’ recommendations are the need for MDBs to more effectively catalyse and mobilise private finance in pursuit of development goals.

Why does mobilisation matter? Here, we first take a look at what the IEG said about private sector mobilisation, before outlining three changes that are needed if we are to better understand the mobilisation of private capital and ultimately drive changes that will result in its growth. In short, we need a workable definition and estimate of catalysed private capital, reforms to how mobilisation is conceived and measured, and increased transparency of mobilisation data.

Welcome ambitious targets

The second volume of the IEG report recommends that:

MDBs should work systematically with the private sector to increase private financing by an additional $500 billion by 2030 including by increasing total private capital mobilization from $60 billion to $240 billion, and making concerted efforts to catalyze a significant volume of additional private finance. This target will be higher or lower for different institutions depending on their context, with higher mobilization rates for private lending arms of MDBs and catalytic agencies like the Climate Investment Funds, and lower rates for agencies that focus more on LICs.

This ambitious target should be welcomed. The additional policy recommendations, including increasing the use of guarantees and making the Global Emerging Markets (GEMS) risk database more transparent, are useful to identify how current mobilisation levels may be increased. It is also helpful to see a target for catalysed capital; to date there has been insufficient attention paid to the ways in which MDBs can help to create the conditions for increase private sector investment in EMDEs. An implied target of US $260 billion (the remainder of the overall target of US $500 billion) suggests that catalysed capital may be greater in volume than mobilised capital.

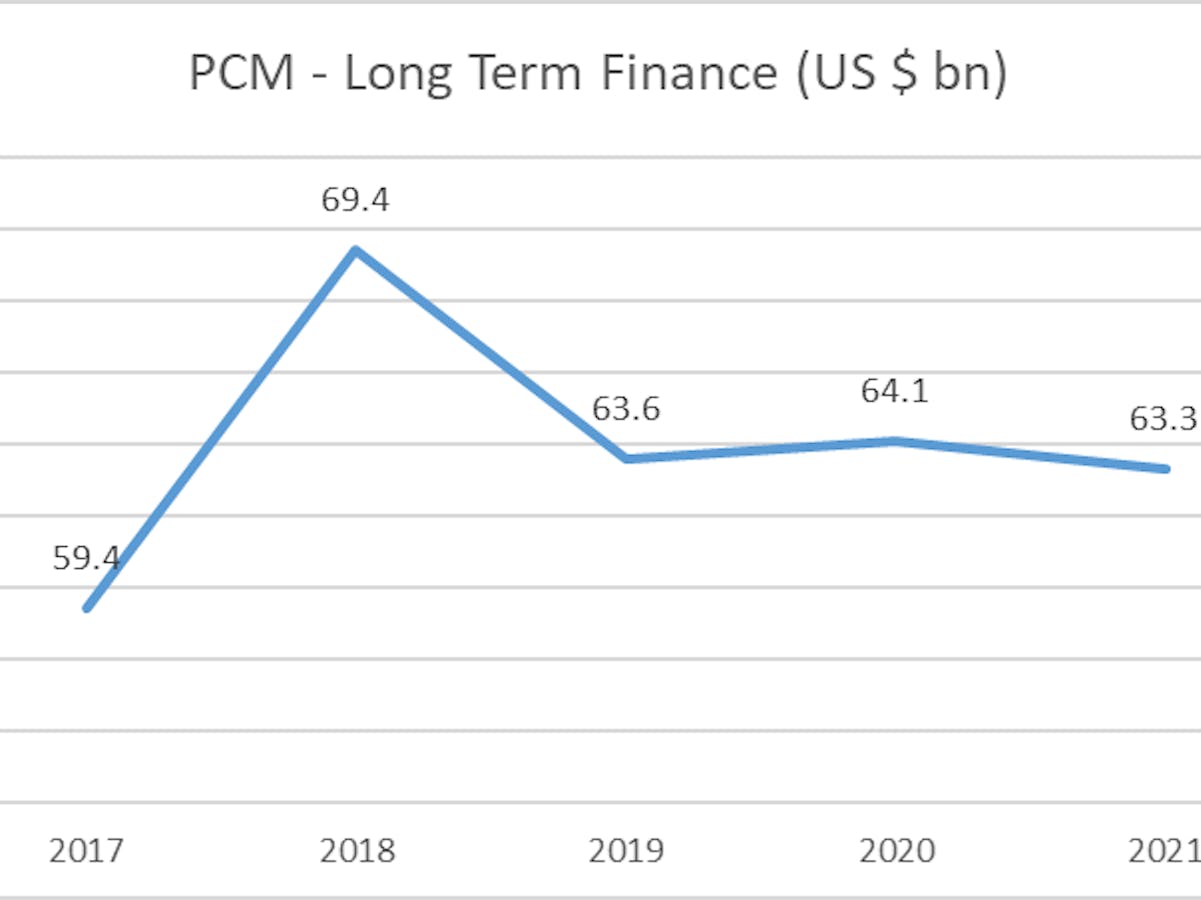

Addressing recent stagnation

We cannot escape the uncomfortable fact that the volume of private capital mobilised by MDBs has largely stagnated over recent years. Having reached a high point of US $69.4 billion of private capital mobilised in 2018, volumes have since hovered in the US $63 billion to US $64 billion range since then. To some extent, although not entirely, these numbers may be explained by the economic effects of the COVID 19 pandemic. MDBs have, to date, pursued “originate to hold” business models and been insufficiently incentivised to mobilise significant volumes of private capital, while MDB shareholders have failed to ensure that mobilisation is a priority. A fourfold increase in the mobilisation of private capital will not therefore occur unless MDBs adopt new business models such as “originate to share”, are incentivised to mobilise through the incorporation of targets in key performance indicators (KPIs), and are held to account by their owners.

The need to define and measure catalysed capital

The IEG report recognises the role that catalysed capital can play in ensuring private investment helps to address international objectives, including the sustainable development goals (SDGs). But what is catalysed capital and how can it be measured? Unfortunately, there currently is no adequate answer to this question. The first volume of the IEG report describes the catalysing of capital as:

measures that unblock private investment at the macroeconomic or sectoral level (such as through policy and regulatory changes or institution-building), through complementary public investment or through project development support (such as technical assistance, feasibility studies or early-stage risk capital).

The relationship between MDB activity and private investment can be conceptualised as being on a “spectrum of attribution” in which the causal linkages between the former and the latter vary in strength. Private capital mobilisation would fit in the medium (indirect mobilisation) to strong (direct mobilisation) portions of the spectrum, while catalysed capital would occupy the low portion of the spectrum. The low attribution strength for catalysed capital has perhaps dissuaded MDBs from systemically measuring and disclosing data related to catalysed capital. The MDBs that contributed to the inaugural 2016 MDB Joint Report on mobilisation committed to “continue to explore ways to measure and report on this broader private investment catalyzation”. However, little progress appears to have been made on this commitment to date.

Recognising the current realities of attribution it would be advantageous to agree not only on a definition but a set of guidelines for catalysed private capital – recognising that any measurement is going to be more art than science. A clear and explicit recognition that catalysed private capital data tends towards estimation would possibly make MDBs more comfortable with disclosing these figures.

The need for a better measure of mobilisation

In addition to the need to define and measure catalysed private capital, there is a pressing need to update the current methodologies for measuring private capital mobilisation. Over the last decade, two methods of measuring mobilisation of private capital have emerged; an OECD approach and an MDB approach. While both approaches have made valuable contributions for understanding mobilisation, there is growing recognition that neither approach satisfactorily defines or measures mobilised private capital in a manner that captures all of the ways in which MDBs can leverage private capital.

The OECD and MDB methodologies focus on mobilisation that takes place through co-financing of individual investments. In the case of direct mobilisation, this involves a formal arrangement between an MDB and a private investor, while in indirect mobilisation MDBs are understood to have encouraged private investment by their presence in a deal, in absence of a formal agreement. However, neither methodology considers the possibility that mobilisation may occur either at different points during an investment cycle or at scales larger than single assets. Recent publications from British International Investment and Neil Gregory have emphasised the fact that mobilisation may also occur during or at exit from an investment, and may also be achieved through balance sheet and multiple asset mobilisation.

Why is it important to better capture all methods of mobilising private capital? If we wish to increase the scale of private capital mobilisation – on which there seems to be broad agreement – then it is imperative that we are able to identify the mechanisms that most efficiently contribute to this goal. Since the current methodologies do not measure mobilisation throughout the life of an investment, and focus solely on single investments, we have little evidence regarding the effectiveness of these mechanisms relative to others. Improving the measurement methodology will thus allow analysts and policy makers to guide MDB business models in a way that could maximise future mobilisation volumes.

It is of course possible that expanding the definition of mobilisation will result in larger volumes of mobilised capital being counted with no discernible change in the operations of MDBs. With this inflationary tendency in mind, it may be necessary to revise the targets set out in the IEG report upwards in light of new evidence.

The need for better disclosure of mobilisation data

Finally, improved measurement of private capital mobilisation will only be of value if we see simultaneous improvements in the disclosure of related data. Current disclosure by both the OECD and MDB Joint Reports lack the requisite level of detail to allow meaningful analysis of what works and what doesn’t. The MDB Joint Reports are typically limited to portfolio-level reporting, with sectoral disaggregation limited to the infrastructure sector. OECD reporting is marginally more disaggregated although limitations still exist.

At a minimum, mobilisation data disaggregated by sector, instrument, and geography is necessary to improve transparency. Ideally, mobilisation data would be fully disaggregated, particularly to allow private sector investors insights into the composition of existing deals and to provide a degree of market confidence to increase private participation in MDB investments. We understand MDBs and their clients hold concerns around data ownership and commercial confidentiality which may necessitate a degree of anonymisation in the publication of fully disaggregated data.

Our work to address these needs

At Publish What You Fund we are currently trying to address each of these three issues through our mobilisation transparency project. We are currently in discussion with a range of stakeholders, including MDBs and DFIs, their shareholders, the private sector, and industry experts, to understand the opportunities and barriers to improving the measurement of catalysed and mobilised private capital, and to increasing the transparency of resulting data.

Early discussions and roundtable events that we have held have indicated a broad-based recognition that, while the existing methodologies have served a purpose, they are in need of reform to capture the evolving business models of MDBs. There has also been acknowledgement that opportunities exist to improve the disclosure of private capital mobilisation data.

As we move forward, we will be developing a set of proposals aimed at improving measurement and disclosure of mobilisation data. We aim to launch these proposals in time for the World Bank Spring meetings, so watch this space.